Virtue is a commonly touted aspiration of a classical education—for good reason. An education that forms virtuous students is desirable.

What happens, though, when we make virtue the goal instead of a natural byproduct of the educational process?

Overemphasizing virtue as a measurable outcome can become a dangerous path for classical Christian educators. If we only focus on producing outwardly moral students, we might miss a precious opportunity to impact future generations.

More importantly, we risk communicating a works-based approach to morality, forgetting that “it is God who works in [us], both to will and to work for His good pleasure,” and that while we may be able to clean up the outside of the cup, we need God’s cleansing work to really change us.

Virtue as a Generational Concept

Language continually evolves, so it’s essential first to define virtue. When discussing virtue or developing virtuous students, people often think of an external characteristic.

Historically, virtue has taken on many meanings. By the mid-1800s, the word “virtue” was increasingly supplanted by the word “morality” in published works. The concept of virtue as a Gospel trajectory was replaced by the pursuit of morality in itself. Looking good became more important than being good.

But virtue is so much more than just moral excellence—though it certainly is that as well.

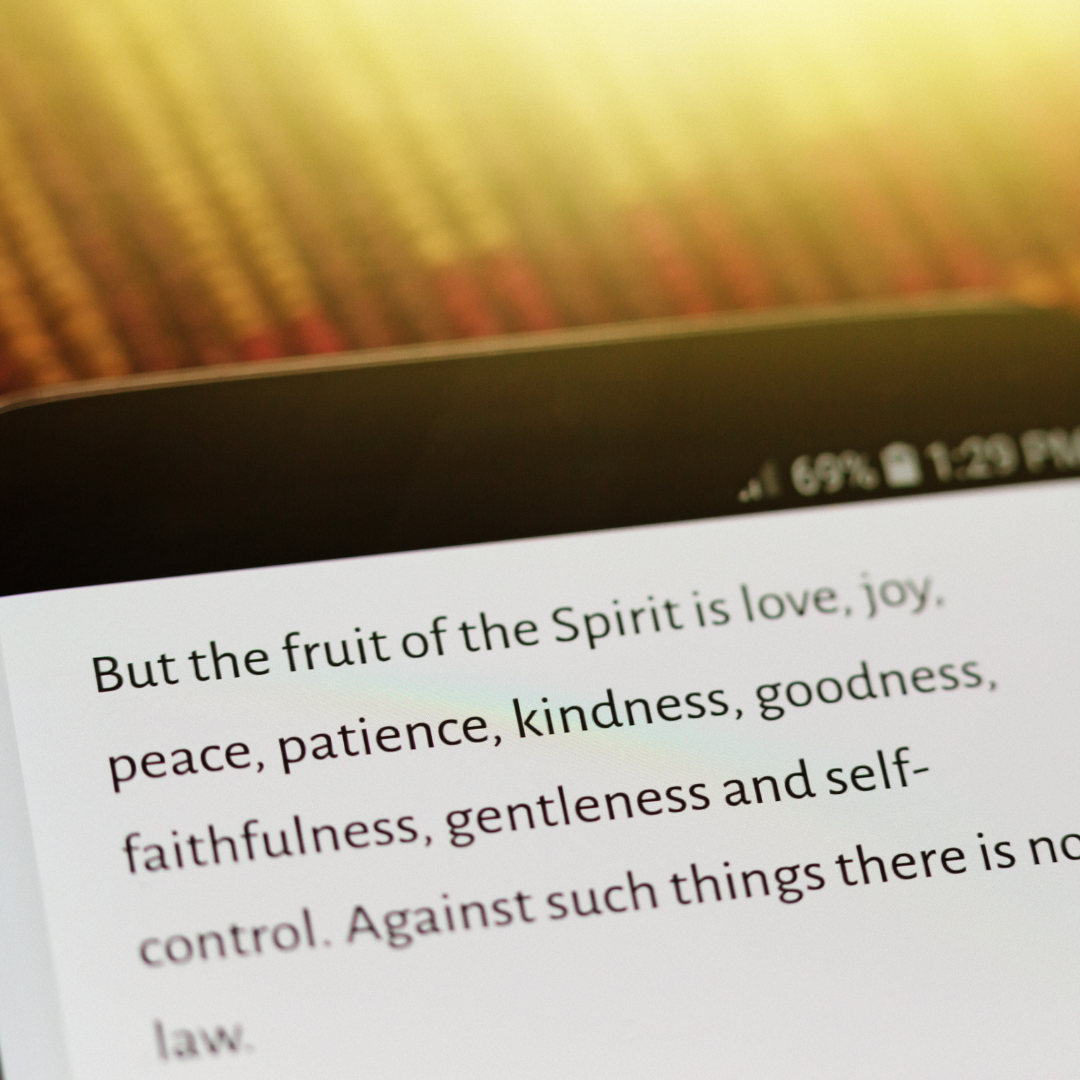

In the same way that a bowl of realistic plastic fruit might look delicious but yield zero nutritional value, outward morality is empty without Christ as the end goal. Biblical images of fruit and fruitfulness are always generational. We will know a tree by its fruit in the same way that that fruit will “reproduce after its kind.” We are called in our lives to “bear fruit, and fruit that remains.” The Holy Spirit bears His fruit in our lives in the form of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.

So when we talk about virtue, we are talking about fruit that reproduces what is true of God in our lives. We are to expect God to perform that reproductive work in us, and as that happens, the “fruit” attracts others to Christ as they see His work in us.

The Danger of Glorifying the Past

In classical education, we are sometimes guilty of trying to recapture the glory of ancient Greece and Rome. We look backward to uphold the great thinkers and writers of the past to emulate their many virtues.

There’s merit, of course, in studying the traits of virtuous men and women in history. But if virtue is something we try to develop ourselves—or encourage our students to develop in themselves—it’s just plastic fruit.

If our virtue doesn’t come from God working in us, it’s empty. Only through the transformative work of the Holy Spirit can we experience genuine, enduring virtue. Empty virtue certainly does not lead to generational impact. As Christ’s followers, we must think of virtue not as something of the past but through the lens of its long-term future impact. Fruitfulness is generational because God’s purposes for us on earth are generational.

But perhaps an even more immediate concern is all that we miss in the present when we pursue virtue through our strength. A life of striving sorely lacks the beauty of a life shaped by the power of the Holy Spirit. When we model a life dependent on the Holy Spirit for our students, we free them from the burden of a works-based faith.

“When we model a life dependent on the Holy Spirit for our students, we free them from the burden of a works-based faith.”

4 Ways to Avoid Teaching False Virtue in the Classroom

So, as educators, how do we avoid the trap of teaching empty virtue? How do we create an environment that nurtures an enduring virtue instead of simply graduating outwardly moral students?

First and foremost, we model humility. As educators, teaching should always be in the service of our students, not to display our own knowledge.

We know our audience. Language matters deeply, and it is our job to avoid misunderstandings or contribute to devaluing concepts like virtue.

We acknowledge that God is the one at work. If we are faithfully pointing our students to truth—including the truth that all truth is rooted in the character of God—we can expect virtue as a byproduct, but we ourselves cannot bring it forth in our students.

We remember that our students are not our homework. We must be careful to remember that the presence—or lack—of virtue is not a reflection of our teaching. Once again, God is the only one who can develop enduring virtue.

If we treat education as a way to puff up knowledge and human virtues, we’re setting our students up for failure. Only when we point them to the truth of the gospel can we leave a Kingdom legacy that will last.